Wearing a black dress, dancing across the interior of an urban mosque and waving an LGBTQ+ flag, Berfin Celebi—formerly known as "Kurdische Kween”—wants to be clear: her mosque is open for business. “Because many believe it is closed,” the caption on her TikTok video reads, Celebi believed it was time to spread the news.

The mosque in question? The Ibn Rushd Goethe Mosque in Berlin, Germany, which opened in 2017 to promote a “a progressive and inclusive Islam,” allowing women and men to pray together and accepting LGBTQ+ members.

But in October 2023, the mosque was closed after security authorities arrested several men from Tajikistan associated with the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISIS-K) who were plotting attacks in Germany—including concrete threats against the Ibn Rushd Goethe Mosque, which they called a “place of devil worship,” and its initiator and co-founder, former German lawyer Seyran Ateş. It remained shut through the end of 2024.

Celebi, a German-Kurdish transgender woman who became known for her sometimes-provocative social media content as a drag queen before her gender reassignment transition, is proud of her now re-opened mosque and is not afraid to show it.

And to critics who call it a “fake mosque,” Celebi and those who have resurrected the project want everyone to know they are ready to welcome queer people once again.

Making Mortals into Martyrs

Charlie Kirk, the 31‑year‑old activist, pundit, and founder of Turning Point USA was one of the most visible voices blending evangelical Christian identity politics with right‑wing populism in the United States. When he was fatally shot while speaking at Utah Valley University on September 10, more than merely “a divisive figure in right‑wing circles” was killed. Kirk was a polarizing public persona across the U.S., known for his provocative rhetoric on religion, race and gender (among other things). His voice carried both influence and animus, drawing fervent support and fierce criticism.

And following his death, he became a martyr.

In the immediate aftermath of his killing, many Kirk supporters—new and old—framed it as spiritual warfare, portraying the shooting as an attack on faith and moral order. His widow, Erika Kirk, declared that his death and legacy would echo “like a battle cry,” and that he “will stand at his savior’s side … wearing the glorious crown of a martyr.”

Pastors, evangelical leaders and everyday Christiansechoed these themes online, saying “martyr blood has reached the throne” and calling for “Gods army” to rise and for followers to “carry on his mission,” warning that the forces opposed to Kirk were spiritual adversaries. Some invoked the words of early Christian apologist Tertullian, who wrote that “the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church,” by saying the death of “Saint Charline Kirk’s martyrdom” would spark a revival.

Alongside spiritual rhetoric came calls for reprisal and retribution: social media quickly filled with posts from far‑right activists suggesting Kirk’s death demanded vengeance and that the political left bore responsibility, implicitly or explicitly. Some posts framed it in apocalyptic terms, speaking of an impending “civil war” to “restore moral clarity.”

The move to make Kirk into a martyr is not unique. It’s a pattern repeated across time and place: when a public figure with religious and political identity dies violently, their death can be transformed into a symbol, merging grief with grievance, spiritual meaning with political mobilization and martyrdom with Other-ing and calls for retaliation.

Martyrs are hailed as heroes, canonized in murals and at vigils. And through hashtags and hushed prayers, their deaths serve as focal points for collective identification, belonging and action.

What do we have to learn from how Charlie Kirk was made into the latest Christian martyr?

Envisioning an "Atlantic Crescent" with Historian Alaina Morgan

How do you imagine different worlds?

According to historian Alaina Morgan, for African descended, or Black, people in the twentieth-century Atlantic–the interconnected system of Europe, Africa, and the Americas that emerged following the European colonization–it meant drawing on anti-colonial and anti-imperial discourses from within and beyond the worlds of Islam to “unify oppressed populations, remedy social ills, and achieve racial and political freedom.”

In her eponymous new book, Morgan envisions the “Atlantic Crescent” as a geography within which to understand the significance of Black Muslim geographies of resistance, occurring “at the intersection of, and influenced by” three overlapping diaspora phenomena: Black American migrant laborers who moved to the United States Northeast and Midwest in the years during and after World War I, Afro-Caribbean intellectuals and immigrants who relocated to the US in the early twentieth century, and newcomers from the Indian subcontinent who arrived in the same period.

Moving, and balancing, between particularist practices and universalist visions, “visible elites and rank-and-file practitioners,” the US and the Anglophone Caribbean, Morgan argues these diasporas merged continents, inscribed populations miles apart into the same histories, and brought communities divided by distance into intimate contact with one another through shared political visions, religious beliefs, and everyday interactions.

In a recent Q&A, Morgan talks about how she theorizes this “Atlantic Crescent” and what we might have to learn about Islam, the Black Atlantic and religion in general by thinking in, with and through it.

Astronism, the Space Religion: An Interview with Founder, Cometan

Humans have long been drawn to space as part of our search for meaning, significance and security. But what if space could be the source of our salvation?

It is this question that led Brandon Reece Taylorian, widely known by his mononym Cometan, to start a new religion: Astronism.

From astrology to astrotheology, from questions of how to practice religions ensconced in Earth’s realities and rhythms to the context of outer space or life on other planets to the creation of new religious movements, spirituality and space exploration have long been intertwined.

It is Astronism, perhaps, that has taken the relationship between outer space and religion to its logical limit. At the age of 15, Cometan began to craft an astronomical religion that “teaches that outer space should become the central element of our practical, spiritual, and contemplative lives.”

“From my perspective, how religion and outer space intersect is crucial to understanding the future of religion,” Cometan, who is also a Research Associate at Lancaster University in the United Kingdom, told me. “Outer space is the next great frontier that will reshape the human condition, including our religions.”

To that end, Cometan has contemplated how space exploration might produce new forms of insight, revelation and spiritual experience.

“The further we dare to venture beyond Earth, the more our beliefs about God and the universe will transform. I think that we need new and bold religious systems that will inspire our species to confront and overcome the challenges of the next frontier,” he said.

“As an Astronist, I define outer space as the supreme medium through which the traditional questions of religion will be answered.”

In this edition of “What You Missed Without Religion Class,” I feature a Q&A with Cometan about Astronism and what we might have to learn about religion – and how we define and study it – through his experience founding a new tradition drawn from the stars.

Telling good religion stories

Religious, spiritual and faith-inspired actors have long shaped public responses to some of society’s most urgent shared crises—from welcoming the stranger to caring for creation. Yet in much of the media coverage around issues like immigration, the economy, gun violence, and the environment, engaged voices of faith are often oversimplified, sidelined, or portrayed in a critical manner.

But what if we focused on good religion stories instead?

In a forthcoming anthology combining journalistic narrative with social-scientific reflections, titled Engaged Spirituality: Stories of Religious Resilience, Inspiration, and Pursuit of the Common Good, I and 17 other authors explore the power of telling such stories. But with an unexpected twist. Or you might say, a surprise ending: that telling good religion stories helps us to look beyond the present, imagine a new repertoire of the possible, and rise together to advance vital conversations around some of the most critical issues of our time.

The anthology emerged out of the Spiritual Exemplars Project, sponsored by the University of Southern California’s Center for Religion and Civic Culture, which involved a team of journalists and researchers profiling 104 spiritually-engaged humanitarians across 13 faith traditions and 42 countries.

The exemplars, individuals motivated and sustained by spiritual values, beliefs, and practices to serve humanity, included a nun who performed the first Buddhist same-sex wedding, a Jewish lay leader who served more than 2 million meals to food-insecure college students, a priest who helped rescue 150,000 distressed refugees in the Mediterranean Sea, a Jain who served more than 400,000 people in 400 Sri Lankan villages and a Latina convert who founded the first shelter for Muslim migrants at the U.S./Mexico border.

Their lives, inspired by African Religious traditions, Baha’i precepts, Protestant ethics, Humanist altruism, and Indigenous spirituality, highlighted some of humanity’s highest shared values in pursuit of the common good.

During the project, team members realized they were not only gaining insights about how spiritually engaged humanitarians understand their lives and work, but about how religious values and spiritual practices inspire and sustain social action on a larger scale. This anthology is an outgrowth of that process, taking readers on a journey to meet people doing extraordinary work and to share their life trajectories, traumas, and triumphs.

Is The Christian Right Coming For Europe?

If you’re anything like me, you pay attention when an e-mail is marked “URGENT!!”

The particular e-mail I have in mind carried a subject line that was direct and equally attention-grabbing: “Christian nationalism is coming for Europe.”

The content was a single link, to an article written by United States journalist Katherine Stewart for The New Republic on the rise of the Christian Right in the United Kingdom. In it, Stewart tells of how she believes a form of hyper-patriarchal, homophobic and nationalistic Christianity often associated with evangelicals in the US is gaining a beachhead in the UK. The developments there, she writes, “are like a window on the American past.

“This is how things must have looked before the antidemocratic reaction really took hold,” she wrote.

As a correspondent covering European Christians and as a scholar teaching religion in Germany, I’ve tracked some of the developments, institutions and movements Stewart cites. While rumors of the Christian right’s rise in Europe need to be taken seriously, it is also vitally important that the careful observer of religion take note of some of the complexities that have shaped the Christian right’s contours in ways distinct from, if related to, the forms we see taking hold in the U.S.

Sikhi: An Updated Guide

There are more than 27 million Sikhs around the world, which makes Sikhi (also known as Sikhism) the fifth-largest major world religion. Yet the Sikh tradition remains largely unknown to the global community – no other religion of its magnitude is as misunderstood as Sikhi.

The Sikh religion has been underrepresented and misrepresented in the popular media, and these problems have contributed to the serious challenges that Sikhs experience today, including negative stereotypes, discriminatory policies, and violent hate crimes.

This guide — a collaboration between the Sikh Coalition and ReligionLink and updated in 2025 — provides information on the Sikh tradition in order to facilitate better understanding of Sikhs and Sikhi.

Can AI Understand Religion? Students Put It To The Test

Ask E.B. Tylor what religion is and he would say it is, “belief in Spiritual Beings.”

Ask William James and he will tell you it is the “feelings, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude.”

Ask Catherine L. Albanese, and she would say it is “a system of symbols (creed, code, cultus) by means of which people (a community) orient themselves in the world with reference to both ordinary and extraordinary powers, meanings, and values.”

Ask Émile Durkheim, Clifford Geertz or others, and you’d get a different answer from the perspectives of sociology, anthropology, theology, philosophy and more.

But what if you ask ChatGPT?

Well, you get a mix of the above, it turns out.

When I asked my friendly, neighborhood artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot, it defined religion as, “a system of beliefs, practices, symbols, and moral codes that connects individuals or communities to the sacred, the divine, or some ultimate reality or truth.”

In the wake of ChatGPT’s viral launch in 2021, the question of how to integrate AI into the classroom — and the religious studies classroom at that — has been at the forefront of educators’ minds. With the global expansion of machine learning, big data, and large language models (LLMs), AI has the potential to radically impact teaching and learning, revolutionizing the way students interact with knowledge and how educators engage course participants.

There are, however, significant concerns about its ethical use, technology infrastructures, and fair access.

In this post, I share how I recently used AI as part of my pedagogy to help prompt deeper understanding of religion in the United States – and what we might have to learn from chatbots about how we define and discuss religion.

The AI Unessay

AI is a technology that enables machines and computers to emulate human intelligence and mimic its problem-solving powers.

The umbrella term “AI” encompasses various forms of machine-based systems that produce predictions, recommendations or content based on direct or indirect human-defined objectives. Based on

LLMs, AI generators like ChatGPT, Jasper or Google Gemini are tools that have been trained on vast amounts of data and text to provide predictive responses to requests, questions and prompts inputted by users like you, me or our students.

As with other advances in technology — from mobile phones and social media to enhanced graphics calculators and Wikipedia — educators have responded to AI in various ways. Some have moved quickly to ban its use and bemoan the submission of essays and other coursework clearly created with the help of AI.

Others have moved to integrate AI into their religious studies pedagogy, inviting students to create videos or infographics with the assist of AI to explain the elements, and role, of rituals to stimulate class discussion or to treat “AI as a tool for lessons that go beyond academics and also focus on the whole person.”

When I recently taught a course on American religion, I decided to assign what I called an “AI Unessay.”

The usual unessay invites students of varying learning modalities and expressions to create final projects that demonstrate their grasp of course material and discussions beyond the traditional essay. These can be hands-on demonstrations, mini-documentaries, artistic visualizations, performative projects or social media campaigns.

The AI Unessay invited course participants to design a set of prompts for an AI generator (e.g., ChatGPT) to write a 2,000-word essay on a topic in American religion, broadly defined. Then, participants were asked to write their own critical response to this AI essay, analyzing its strengths, weaknesses, sources and the process itself.

AI’s Religious Illiteracy

Students chose a variety of topics to cover, from religious themes in metal music and superhero comics to the “trad wife” trend among members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and digital seances.

Throughout the semester, I worked with participants to refine their topic selections, come up with AI prompts and conduct secondary-source research and firsthand “digital fieldwork.”

Meanwhile, course lectures and readings were provided to supply helpful context on how each of these themes might be better placed within the wider currents of American religion and its

In a recent classroom experiment, students found, like many others, that AI responses were often biased, inaccurate, or even harmfully ignorant. | Image created in Meta AI for Patheos.

intersections with U.S. politics, economics and society.

Not all course participants opted for the AI Unessay. Others wrote traditional papers or put together a different kind of creative final project. But the majority of students opted for the AI-based project, saying they not only wanted to learn more about how to productively, and critically, work with AI, but wondered whether the technology was up for the challenge of understanding, parsing out and pontificating on America’s religious diversity.

Though participants did learn some new information from the AI essays and discovered some data they hitherto were unaware of, they were — on the whole — disappointed with the results. They found, like many others, that AI responses were often biased, inaccurate or even harmfully ignorant.

They also found that citations and sources were a decidedly mixed bag, with the chatbots often manufacturing fake data and made-up books or articles.

And finally, numerous students reflected that it was a challenge to get the AI chatbot to write at the appropriate length (2,000 words). The technology was often too efficient, churning out well-structured, but far too brief, answers to questions about metal music’s spiritual intimations or the nuances of the “trad wife” trend on TikTok. When asked to elaborate, participants found AI was overly repetitive or even fabricated false information or created concrete details and data that were inaccurate or exaggerated. It also regurgitated implicit and explicit biases against marginalized religious communities or intra-faith minorities.

As one participant summed it up, “I found AI to be more religiously illiterate than me, which is saying something!”

Where to from here?

Asked to consider why AI was found wanting in its accuracy in depicting American religious diversity, participants surmised that because AI is trained on what internet publics “know” and share about religion, it is just as religiously illiterate as the rest of us. They suggested it takes students of religion who are paying careful attention to help it along, correct its mistakes and continue to critically question the just-so narratives about religion, religions and the religious that can be found online.

In other words, participants discovered how AI amplifies and compounds some of the worst in religious illiteracy.

Writing for the Religion, Agency and AI forum, digital religion scholar Giulia Evolvi reminds us that in an age of hypermediation, “religious communication, like all modern communication, is no longer mediated linearly. Instead, digital media amplifies and reshapes it, creating intensified networks and narratives.”

Thus, in an age when more people will turn to AI to answer their questions about religion and spirituality, it is important that we engage with the technology, critique its biases and weaknesses and continue to pay attention to the ways humans employ the concept of “religion” to make sense of the world around them and their place in it.

Even with the advent of AI technologies — and religious studies students’ use of it — the why of studying religion doesn’t change. Religion remains interesting, intricate and important.

We might just need to shift some of the ways we go about making sense of it and adapt our classrooms and conversations accordingly.

When religious leaders die

For me, Jimmy Carter’s death came too soon.

Not necessarily because of his age. He lived to the ripe old age of 100 and, in many respects, lived those years to the fullest.

No, and if I may be crass for a moment, Carter passed before I had a reporting guide ready for reporters looking to cover the faith angles of his life and legacy.

You see, as Editor for ReligionLink, I put together resources and reporting guides for journalists covering topics in religion. Each month, we publish a guide covering topics such as education and church-state-separation under Trump, faith and immigration or crime and houses of worship.

Early in 2024, I started to put together a guide to cover the passing of Jimmy Carter. Serving as Editor is only a part-time gig, and it usually takes all the time I have dedicated to the role to produce a single, monthly guide. But on the side, I started to make notes, identify sources and build a timeline for Carter’s life and legacy.

When he passed on December 29, 2024, the guide was not ready. Nor would it be in the matter of days necessary for it to be useful. So, the opportunity came and went. The draft of the guide to covering Jimmy Carter’s passing tossed on the editing floor.

The missed occasion, however, inspired me to work ahead more intentionally on guides for other famous faith leaders. The process of putting such guides together led me to reflect on what it means to remember, and report on, the passing of prominent figures in religion.

Covering, and Questioning, Anti-Christian Persecution

If you report on religion long enough, you’re bound to be called an anti-Christian bigot at some point in time.

In my 14 years of reporting, I’ve been labeled an atheist agent for my coverage of a book on how Jesus may have been a vegetarian, denounced as a prejudiced partisan as I covered instances of clergy abuse in Houston, Texas, and much worse for my writing on neo-Nazi ideology and racism among Lutherans in Germany and the U.S.

In each case, the critique of my writing was less about the coverage or claims therein, but much more to do with a feeling that anti-Christian bias — and even persecution — in the media is not only real but rampant.

When it comes to the issue of anti-Christian persecution itself, coverage in the media can sometimes swing between two magnetic poles. On one end are those who are convinced that such persecution is the most pressing contemporary human rights issue. On the other are those who equate such statements as melodrama, with little grounding in the lived reality of most communities worldwide.

Journalists covering the issue might be swayed depending upon their sources, who often have a stake in arguing one way or the other.

To best cover the matter of anti-Christian persecution, or to address it when it comes up in critiques of our coverage, reporters have to make two things clear: 1) many individuals and communities across the globe are vulnerable because of their identification as Christians and 2) that the extent of anti-Christian persecution is not as widespread or as grievous as some make it out to be.

To help navigate how to cover particular cases and claims, I recommend journalists consider issues related to power, the shift from “privilege to plurality,” and how Christians use the idea of persecution as a way to make sense of their faith in the 21st century.

If Piety Is Always Political, Who Then Is A Saint?

On the outskirts of Naples, in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius, lies the sanctuary of Madonna dell’Arco in Sant’Anastasia.

The walls of the shrine are covered in painted, votive tavolette — little, painted boards given as an offering in fulfillment of a vow (ex voto) and featuring devotional scenes and images of the Virgin Mary holding the infant Christ.

One of my favorites features a man in bed, with a heavily bandaged leg, his small children and wife praying to the Virgin and Child as they appear amidst a veil of clouds from their throne in heaven.

It is, in many ways, a visual embodiment of traditional notions of piety, defined as dutiful devotion to the divine.

But as I teach in my religious studies courses, piety can take a variety of forms.

It can be visual and sartorial, both highly personal and politically charged. More than an individual’s particular practice of religious reverence, piety is a socially defined and structured response to one’s emotional, social and material context. And in a time of political upheaval, social uncertainty and ecological anxiety, it might do well to revisit piety and its varieties.

Reporting on faith in polarized times

In a slight departure from my usual column at Patheos (“What you missed without religion class”), I was asked by my editors to respond to the following prompt, as part of their new initiative on Faith & Media:

“Faith Amid the Fray: Representing Belief Fairly During Polarized Political Times - Explore the role of media in shaping perceptions of faith during politically charged times. As we have a government in transition and the world becomes less stable, how should the media work to accurately reflect faith’s place in all this? ”

As outgoing president of the Religion News Association and Editor of ReligionLink — a premier resource for journalists writing on religion — I’ve spent time thinking about what religion reporters write about and how it’s best done.

Looking back on my 14 years on the beat, and looking ahead to the role of news media in shaping perceptions of faith in the politically charged times we have ahead of us, I believe religion reporters have the opportunity to approach the next year with “curiosity” — as The New Yorker’s Emma Green put it — and recommit to the balance, accuracy and insight that best characterizes our beat.

I encourage all those who care about faith and media in polarized times to take a deeper look at the link below…

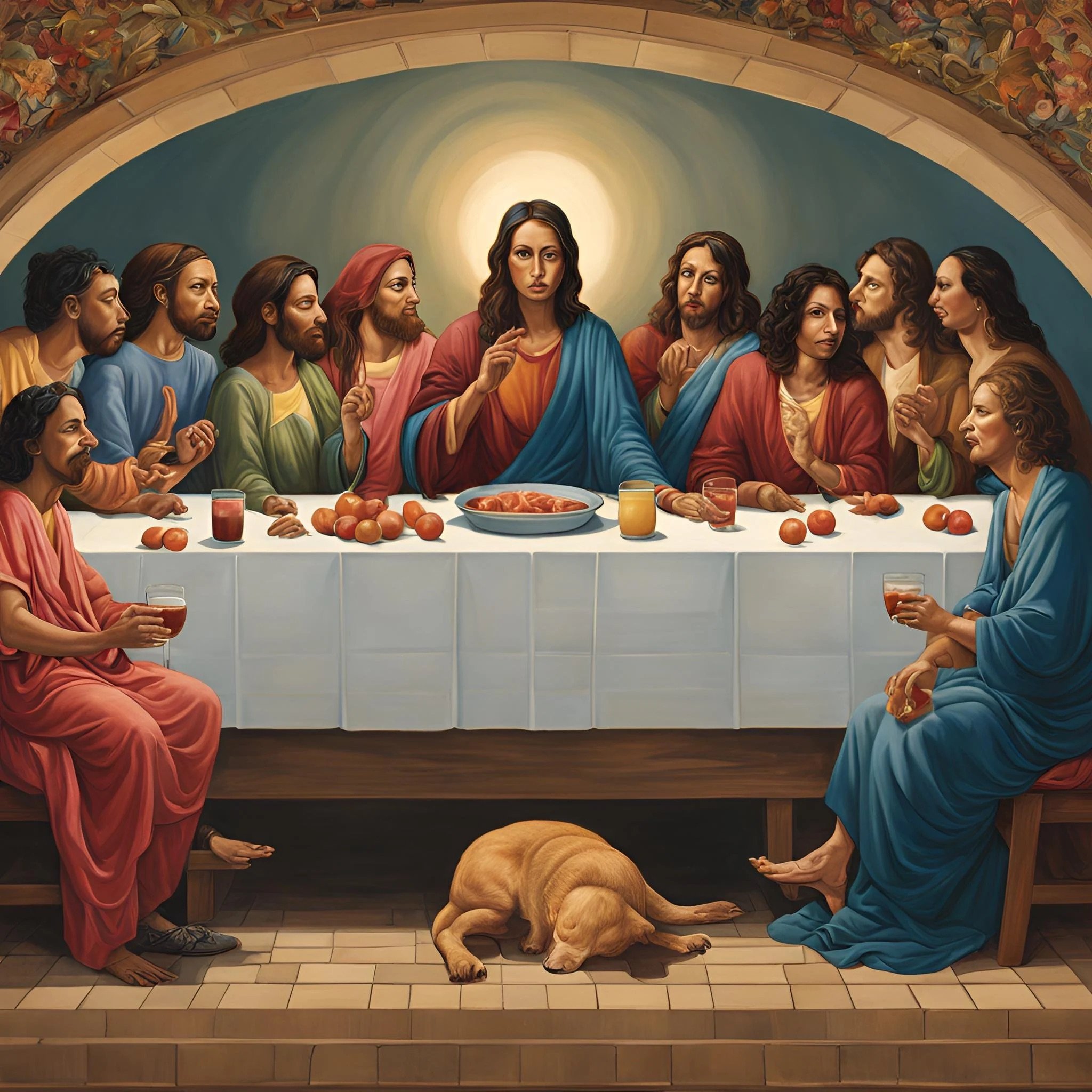

Image And Power, Satire And Sacrilege At The Paris Olympics

When I teach a religious studies class, I try to pull something from the headlines to use for discussion. You know, something religion-y to get students thinking about religion’s continuing ubiquity and importance in the world today.

Had I been teaching a class at the end of July 2024, there would have been only one option for that thing: the opening ceremony of the Paris Olympics.

Not the bells ringing at Notre Dame Cathedral and not Sequana, goddess of the river Seine, galloping in gleaming silver with the Olympic flag. Worthy topics, to be sure. But none was more worthy of discussion — if social media were the measure of things — than a living tableau of LGBTQ+ performers posing in what seemed to be (or…possibly not) a recreation of Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Last Supper.”

It created some conversation and controversy, to say the least. And rather than adjudicating the right- or wrongness of the artistic choice, the ins and outs of the potential offense, whether the portrayal was Ancient Greek or Renaissance Italian, or the dynamics of French secular culture, global Catholicism and U.S. evangelical culture (again, all worthy topics), I would have used the kerfuffle as a case study in the power of the image and the power of satire in the world of religion.

The power of image

With or without religion, images are powerful. They move us to anger, they move us love; they move us to buy, they move us to believe.

And in his eponymous book, religion scholar David Morgan discusses the power of the “sacred gaze” — a way of seeing that invests an object (an image, person, time or place) with spiritual significance. Across a variety of religious traditions, Morgan traces how images in different times and spaces convey beliefs and produce religious reactions in human societies – what he calls, “visual piety.”

As human products, images and religious ideas have grown together, with some images having the power to determine personal practice and identifications, rituals and notions of sacred space. As “visual instruments fundamental to human life,” images have their own materiality and agency. Think of the ubiquitous statue of the Buddha sitting in backyard or the glittery gold calligraphy of “Allah” or “Muhammad” hanging over a family’s living room; the brightly colored images of Ganesha and Krishna or a copy of Eric Enstrom’s “Grace” hanging in kitchens and cookhouses across the U.S.

Each of these images serve as markers of a whole range of social concerns, devotional piety, creedal orthodoxy or gender norms.

So too with da Vinci’s “Last Supper.” As one of the most well-known religious images the world over, the painting is not a part of any Christian canon. It isn’t even an accurate representation of what the Last Supper, as recorded in the Christian Gospels, would have been. Jesus’ disciples were not Renaissance European white men, they were probably not pescatarians, nor were they seated on one side of the table (or seated at that kind of table at all). But as a myth we knew we were all making, and as the National Gallery’s Siobhán Jolley pointed out on X, the painting morphed from being a sign (a painting portraying an interpretation of biblical texts) to a signifier (a bearer of meaning so pronounced that it came to visualize Jesus’ last meal with his followers for many).

And in our contemporary culture(s), such visual cues carry a particular kind of power. In a highly visual society, bombarded by the rapid consumption of images on screens of varying size and intensity, images can transcend one context and speak to many — as did the recreation of da Vinci’s “Last Supper” (or…maybe not) when it resonated both positively and negatively with so many.

As a visual quotation of a popular image, we translated its meaning and the image spoke with power to various communities and subcultures. It tore people up and took the internet by storm. It manifested opprobrium and offense, celebration and adulation, as it was read as a sacrilege of the highest offense or as a symbol of vibrant tolerance and pleasing subversiveness. Along the way, it created a whole range of responses, on what is and what is not offensive, what is and is not idolatry, what is and is not Christian privilege, what is and is not persecution; the list could go on and on.

For all that it was (or was not), the Opening Ceremony moment (and it was, after all, but a blip on the screen) illustrated once again the power of religious images, even in increasingly secular societies.

The power of satire

In addition, whatever the performance was meant to represent, it was almost certainly meant as a form of satire.

A genre with generations of history, religious satire’s power lies in its ability to direct the public gaze to the vice, follies and shortcomings of religious institutions, actors and authority writ large. Whether calling out hypocrisy or corruption, religious satire has been used for centuries to take religious elites or established traditions to task.

Examples of savage satire and nipping parody abound across religious history. From the Purim Torah and its humorous comments read, recited or performed during the Jewish holiday of Purim to "Paragraphs and Periods,”(Al-Fuṣūl wa Al-Ghāyāt) a parody of the Quran by Al-Ma‘arri or the Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer or Robert Burns’ poem “Holy WIllie’s Prayer,” authors and authorities, playwrights and poets have wielded scalding pens to critique what they see as the hypocrisy, self-righteousness and ostentation of religious communities.

As such, satire has been powerful as a means of protest both from without and within religious traditions. For example, the 16th-century rebel German monk and Reformer Martin Luther used his caustic touch to call what he thought were abuses within the Catholic Church to task. Jeering and flaunting his way through theological controversies and the dogmatic discussions of his day, Luther was not one to skirt the issue or back away from using humor and satire to prove his point. In fact, he was well known for his use of scatological references, offending his followers and opponents with vulgar references to passing gas and feces.

Each of these examples shows how satire relies on a combination of absurdity, mimicry and humor to highlight the problems its creators see with religious actors’ or institutions’ behaviors, vices or social standing.

To that end, the opening ceremony’s display was religious satire par excellence, insofar as it pushed a particular social agenda and advocated for certain recognitions for a marginalized community through its exhibition. The living display not only created a stir but captured the public imagination, sparking discussion and debate about Christian privilege, European culture and the acceptance and affirmation of LGBTQ+ individuals in religious communities. In this way, religious satire can also help create community and a sense of belonging among those who are in on the joke and jive with the critique embodied in the satire.

The persistent power of religion

The debate around the tableau will (hopefully) die down in the days and weeks to come (and perhaps already has in a media cycle that serves up a fresh controversy every 24-hours). But if I were to point to just one lesson in my religious studies classroom, I would highlight how the scene — for all it was or wasn’t — proved once again the power of images and satire in the field of religion.

It is another case study in how, even at supposedly “secular” events in a decidedly “secular” country, religion — and the primary and secondary images and satire thereof — remains persistently present and ubiquitously potent. And that, dear students of religion, is something to keep in mind for the next controversy, which is sure to come sometime soon.

Image via Unsplash.

Culture Wars 3.0

How we identify — according to race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion or gender — is at the heart of hundreds of bills in legislatures across the country. And as U.S. voters across the political spectrum gear up for the 2024 presidential cycle, debates are intensifying about how to define the nation’s values around these issues.

Just weeks ago, the U.S. Supreme Court announced it will hear arguments on the constitutionality of state bans on gender-affirming care for transgender minors.

The issue has emerged as a big one in the past few years. While transgender people have gained more visibility and acceptance in many respects, half of U.S. states have instituted laws banning certain health care services for transgender kids.

In recent years, voters have been particularly fired up about the lessons and books that should, and shouldn’t, be taught to children about their bodies or the nation’s past. But those culture wars have also come to corporate America and college sports.

These renewed culture wars have take over everything from local school board meetings to state legislatures and the U.S. Capitol.

In the following, I unpack how we got here and round up stories and sources for going deeper into the culture wars’ decadeslong history.

How then shall we live, when the world is on fire?

Climate change is happening.

I am not a scientist. Nor do I pretend to be. But drawing on information taken from natural sources — like ice cores, rocks, and tree rings — recorded by satellites, and processed with the aid of the most advanced computer processors the world has ever known, NASA experts report “there is unequivocal evidence that Earth is warming at an unprecedented rate” and that “[h]uman activity is the principal cause.”

From global temperature rise to melting ice sheets, glacial retreat to sea levels rising, the evidence of a warming planet abounds. While Earth’s climate has fluctuated throughout history, the current season of warming is happening at a rate not seen in 10 millennia — 10,000 years.

Many of the undergraduate students in courses introducing them to religious traditions — Islam, Christianity or otherwise — have no reservations about climate change and its disastrous effects on the environment and the most vulnerable in human society. In my classrooms, there is a palpable fear about the planet’s future.

It is little wonder, then, that students often ask how religious actors interpret their sacred texts and confessions or how they, in turn, address climate change or engage with the environment.

What they discover can often be disappointing — if not infuriating.

A Cross In The Barbed Wire: Mixed Reflections On Faith & Immigration

In February 2019, Miguel stared out at the San Pedro Valley in Mexico, stretching for miles below him from his position on Yaqui Ridge in the Coronado National Monument. Standing at Monument 102, which marks the symbolic start of the 800-mile-long Arizona Trail, Miguel remarked on how the border here doesn’t look like what most people imagine.

Instead of 30-foot bollards, all one finds is mangled barbed wire to mark the divide between Arizona and Sonora. Here hikers can dip through a hole in the fence to cross into Mexico, take their selfie, and pop back over.

“It’s as easy as that,” Miguel said, with a melancholic chuckle.

But for Miguel’s mother the crossing was not only difficult — it was deadly. She perished trying to find her way to the U.S. across the valley’s wilderness when Miguel was just four years old and already living in the U.S. with his father.

Not knowing exactly where she died, Monument 102 became a makeshift memorial for Miguel’s mother, the obelisk marking the U.S./Mexico border a kind of gravestone. The barbed wire itself even holds meaning for Miguel. “When I come every year to remember her,” he said, “and the knots in the barbed wire remind me of the cross.

“It may sound strange, but that gives me comfort,” he said.

Miguel is far from alone in making religion a part of the migrant’s journey. As migrants move around, across and through borders and the politics that surround them, religious symbols, rituals, materials and infrastructures help them make meaning, find solace and navigate their everyday, lived experience in the borderlands.

With immigration proving a top issue for voters in the U.S. and Europe this year, this edition of What You Missed Without Religion Class explores the numerous intersections between religion and migration.

Feast or fast, food and faith

“You’d think we’d lose weight during Ramadan,” said Amina, a registered dietician who observes the Islamic month of fasting each year in Arizona, “but you’d be wrong.”

Ramadan, the ninth month of the lunar calendar, is a month of fasting for Muslims across the globe. Throughout the month, which starts this year around March 11, observers do not eat or drink from dawn to sunset.

“It sounds like a recipe for weight loss,” Amina said, “but you’d be wrong. I’ve found it’s much more common for clients — of all genders and ages — to gain weight during the season.”

The combined result of consuming fat-rich foods at night when breaking the fast (iftar), numerous celebratory gatherings with family and friends, decreased physical activity and interrupted sleep patterns means many fasters are surprised by the numbers on the scale when the festival at the end of the month (Eid al-Fitr) comes around.

Christians observing the traditional fasting period of Lent (February 14 - March 30, 2024) can also experience weight gain as they abstain from things like red meat or sweets. Despite popular “Lent diets” and conversations around getting “shredded” during the fasting season, many struggle with their weight during the penitential 40-days prior to Easter, the celebration of Jesus’ resurrection.

The convergence of the fasting seasons for two of the world’s largest religions meet this month, and people worrying about weight gain during them, got me thinking about the wider relevance of food to faith traditions.

And so, in two pieces — one for ReligionLink and the other for Patheos — I take a deeper look at how foodways might help us better understand this thing we call “religion” more broadly.

What's behind the rising hate?

At the end of last year, the uptick in antisemitic and Islamophobic incidents in the U.S. and around the globe captured headlines as part of the fallout from the Israel-Hamas war.

Reactions were swift and widespread, as university presidents resigned, demonstrators took to the streets in places such as Berlin and Paris and the White House promised to take steps to curb religious and faith-based hate in the U.S.

The topic of rising discrimination and incidents of hate remains contentious, as political polarization and debate over definitions challenge reporters covering the issues.

But before we come to conclusions, it’s important to consider a) what we are talking about - or - how we define antisemitism and Islamophobia and b) the long arc of “Other” hate across time.

In the latest editions of ReligionLink and “What You Missed Without Religion Class,” I unpack both so we can better understand and react to the surge in hate.

Tomorrow’s religion news, today

At the beginning of last year, I predicted the Pope would be big news in 2023.

While I thought it would be because of his declining health and increased age, it turned out that Pope Francis had big plans to cement his long-term hopes for renewal, which are likely to outlast his pontifical reign.

In 2023, Pope Francis remained busy, traveling widely, convening a historic synod, denouncing anti-LGBTQ+ laws and approving letting priests bless same-sex couples, overseeing the Vatican repudiation of the Doctrine of Discovery and facing various controversies.

For all the above, he was named 2023’s Top Religion Newsmaker by members of the Religion News Association, a 74-year-old association for reporters who cover religion in the news media.

Beyond Francis and the Vatican, there were other major headlines in 2023: the Israel-Hamas war, along with the rise in antisemitic and Islamophobic incidents in the U.S. and around the globe, ongoing legislative and legal battles following last year's Supreme Court ruling overturning Roe v. Wade, the exodus of thousands of congregations from the United Methodist Church and the nationwide political debates over sexuality and transgender rights and the Anglican Communion verging on schism.

While it is one thing to look back on the top religion stories of the year, what about predicting — as I did with the Pope — what will be the big religion news in 2024?

In 2024, we will see ongoing wars in places like Gaza, Ukraine, Yemen and Nargono-Karabakh continuing to capture headlines. So too the state of antisemitism and anti-Muslim discrimination. The ubiquity and uncertainty of artificial intelligence should also be on our radars, as should news related to the intersections of spirituality and climate change, the fate of global economies and how religious communities adapt to the ruptures and realignments associated with an increasingly multipolar world.

For more on my predictions, as well as additional sources and resources to explore, click the link below.

And to go even deeper into 2024’s religion predictions, you can explore my analysis of religion’s role in ongoing conflicts, upcoming elections and more by checking out my column, “What You Missed Without Religion Class.”

Your Favorite Stories from 2023

Each December, Religion News Association (RNA) members vote to select the Top Ten Religion Stories of the Year. This year, journalists on the religion beat chose the Israel-Hamas war and its reverberations as both the top international and domestic religion stories of the year.

No doubt, that is a story that will continue to dominate headlines for days — and months — to come.

Here on the Religion+Culture blog, you too cast your vote for the top stories of the year…even if you were not aware. Each year, I make a brief review of the stories that caught your attention here on KenChitwood.com. After crunching the numbers, I put together a Religion+Culture Top Ten, based on your clicks and views.

This year, you were tracking with some of the top stories around the world. But from time-to-time, you also chose to dig deeper into stories others might have missed. Good on you. From religious facial markings to Bible translation news, Hindu nationalism to religion at the Academy Awards, thanks for nerding out with me in the wide world of religion news.